|

Hendrick Hamel, “Hamel’s Journal and a Description of the Kingdom of Korea” (1668)

Hendrick Hamel (1630 – 1692) was the first Westerner to provide a first hand account of Joseon Korea. After spending thirteen years there, he wrote “Hamel’s Journal and a Description of the Kingdom of Korea, 1653-1666,” which was subsequently published in 1668. Hendrick Hamel was born in Netherlands. In 1650, he sailed to the Dutch East Indies where he found work as a bookkeeper with the Dutch East India Company (VOC). In 1653, while sailing to Japan on the ship “De Sperwer” (The Sparrowhawk), Hamel and thirty-five other crewmates survived a deadly shipwreck on Jeju Island in South Korea. After spending close to a year on Jeju in the custody of the local prefect, the men were taken to Seoul, the capital of Joseon Korea, in June, 1655, where King Hyojong (r.1649 to 1659) was on the throne. As was customary treatment of foreigners at the time, the government forbade Hamel and his crew from leaving the country. During their stay, however, they were given freedom to live relatively normal lives in Korean society. In September 1666, after thirteen years in Korea, Hamel and seven of his crewmates managed to escape to Japan where the Dutch operated a small trade mission on an artificial island in the Nagasaki harbor called Deshima. It was during his time in Nagasaki (September 1666 to October 1667) that Hamel wrote his account of his time in Korea. From here, Hamel and his crew left to Batavia (modern day Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies in late 1667. |

Original text (Dutch)

English translation

|

| Tochiotome | Red pearl | Akihime | Solhyang | Mehyang | Kumhyang | |

|

|

|

crossbreeding of Red pearl & Akihime |

crossbreeding of Akihime & Tochinomine (parent of Tochiotome) |

crossbreeding of Tochiotome & Akihime |

Basil Hall, “Account of a voyage of discovery to the west coast of Corea, and the great Loo-Choo island” (1818)

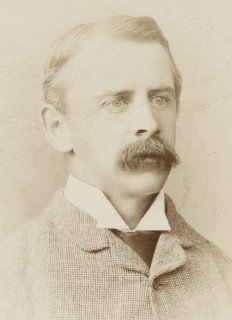

Basil Hall, FRS (1788 – 1844) was a British naval officer from Scotland, a traveller, and an author. He is known for his voyages to the Indian Ocean, China, Korea, Ryukyu, Central and South America and the various places in North America. Internet Archive |

|

Philipp Franz von Siebold, “Nippon” (1832)

Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (1796 – 1866) was a German physician, botanist, and traveler. He achieved prominence by his studies of Japanese flora and fauna and the introduction of Western medicine in Japan. Internet Archive |

Original text (German)

English translation

|

Ivan Goncharov, “Frigate ‘Pallada’” (1858)Internet Archive English translation:Klaus Götze

Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov (1812 - 1891) was a Russian novelist. In 1852 Goncharov embarked on a long journey through England, Africa, Japan, and back to Russia, on board the frigate Pallada, as a secretary for Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin. Goncharov’s travelogue, Frigate “Pallada” began to appear, first in Otechestvennye Zapiski (April 1855), then in The Sea Anthology and other magazines. |

|

Koichi Miyamoto, “The omission of the records of the service by Korean Government and the summary of Korean manners and customs” (1876)Japan Center for Asian Historical Records National Archives of JapanIn 1876, the Japanese Government dispatched Koichi Miyamoto, a Foreign Ministry official to Seoul to discuss “Japan–Korea Treaty”. Koichi Miyamoto was welcomed as the state guest in Korea, and after return home, he wrote this report. The report described the manners and customs of food, clothing and housing of the people of the then Joseon dynasty well. It is very interesting. I extract a part written about “palace cuisine”. |

|

Ernst J. Oppert “A forbidden land: voyages to the Corea” (1880) Internet Archive

Internet Archive

Ernst Jakob Oppert (1832 – 1903) was a Jewish businessman from Germany. |

|

William Richard Carles, “Life in Corea” (1888) Internet Archive

Internet Archive

William Richard entered the Consular Service in 1867, when he was sent as a student interpreter to China. He served in various parts of China from 1867 to 1901. Carles spent some 18 months in Korea. Carles accompanied two other Englishmen. They arrived at Chemulpo from Shanghai on November 9, 1883. After a few days in Seoul, on November 16 they set out to explore the mining areas immediately to the north and east. After being appointed Vice-Consul in April 1884, Carles returned to Korea at the end of April and attended the ceremony in the palace on May 1, 1884, when Sir Harry Parkes presented a letter from Queen Victoria to the King. After the conclusion of the ceremonies, Carles took up residence as Vice-Consul in Chemulpo. He made occasional visits to Seoul, then early in September he was ordered by London to make a survey of the so-far unexplored northern regions, to see if there were business prospects for Britain in that direction. The description about the standard of the then commerce and industry, Japanese advance to Korea and social manners and customs including the position of the women in Korea is rich and interesting. |

|

George W. Gilmore, “Korea from Its Capital” (1892)Internet ArchiveGeorge William Gilmore (1857~?) was an American theologian who stayed in Korea in 1886~1889. He was invited to teach at Yukweon Kongweon in Seoul together with Homer B. Hulbert and Dalzell A. Bunker in July 1886. He was disappointed with idleness of students from yang-ban class and returned to the U.S. in 1889. |

|

George N. Curzon, Problems of the Far East: Japan-Korea-China, Kessinger (1894)Internet Archive George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, KG, GCSI, GCIE, PC, FBA (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), who was styled as Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911, and as Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, and was known commonly as Lord Curzon, was a British Conservative statesman, who served as Viceroy of India, from 1899 to 1905, during which time he created the territory of Eastern Bengal and Assam, and as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, from 1919 to 1924.

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, KG, GCSI, GCIE, PC, FBA (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), who was styled as Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911, and as Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, and was known commonly as Lord Curzon, was a British Conservative statesman, who served as Viceroy of India, from 1899 to 1905, during which time he created the territory of Eastern Bengal and Assam, and as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, from 1919 to 1924.

|

|

Savage-Landor, Henry A, “Corea or Cho-sen - The Land of the Morning Calm” (1895)Internet Archive

Arnold Henry Savage Landor (1865 – 1924) was an English painter, explorer, writer, and anthropologist. Landor wrote in an often witty style. He was born to Charles Savage Landor in Florence, Italy, where he spent his childhood. The writer Walter Savage Landor was his grandfather. He left for Paris at age fifteen to study at the Académie Julian directed by Gustave Boulanger and Jules Lefebvre. He then travelled the world, including America, Japan and Korea, painting many landscapes and portraits and on his return to England was invited to Balmoral by Queen Victoria to recount his adventures and show his drawings. |

|

Jiji shimpō, “You should watch the fact” (1897)Jiji shimpō, an editorial articleJiji shimpō is a Japanese daily newspaper that ever existed. It was founded on March 1 in 1882 by Yukichi Fukuzawa. Yukichi Fukuzawa expected the true independence of Korea that was under pressure of the Qing Dynasty to the last. The original purpose of Yukichi was the stop of the advance to East Asia and its occupation by the great powers of Europe and the United States, and he thought the Japanese armaments had to protect not only one country, Japan, but also the Oriental countries from the Western countries. Therefore he supported the Asian “reformists” such as Kim Ok-gyun of Joseon dynasty eagerly. He allowed Koreans to enter his school, Keio Gijuku, and he came in contact with them while feeling close to them. (wikipedia) The claim of this editorial is different from that of Yukichi. Therefore, it is not thought Yukichi wrote this article. It is thought that Kammei Ishikawa, a main author of “Jiji shimpō ” wrote this. |

| Koreans are originally the people who have been falling into a Confucian toxicosis for several hundred years and can hardly describe their corruption dirtiness of the bottom of heart while always saying the morality humanity and justice. It is the den of the fake wise men together at the top and the bottom, and it is clear that there are no Korean who is reliable even if I compare it with my experience for many years. Therefore, even if you conclude any promise with such a nation, the betrayal breach of promise is their true nature and they do not mind it at all. You have to prepare your mind that the promise with the Korean is invalidity from a beginning, because I often really experienced it from my association with Korea until now. And you only have no choice but to obtain a fruit by yourself. |

Isabella Lucy Bird, “Korea and Her Neighbors” (1898)Internet Archive Isabella Lucy Bird was an English female explorer.

When she was 62 years old in 1894, she visited Korea. For about 3 years since then, Bird had traveled all part of Korea over 4 times.

Then exactly the historical events such as Sino-Japanese war, Donghak Rebellion and Min-pi assassinations, etc. occured successively in Korea inside and outside of the country.

This is the outstanding travelogue, that faithfully tells the disquieting political situation of the Rhee Dynasty’s last years tossed about by the international situation

and the Korean natural face Bird saw such as the traditional climate, the folk customs and the cultural etc. that are left deeply in the Korea in the time right after Korea opened the country.

Isabella Lucy Bird was an English female explorer.

When she was 62 years old in 1894, she visited Korea. For about 3 years since then, Bird had traveled all part of Korea over 4 times.

Then exactly the historical events such as Sino-Japanese war, Donghak Rebellion and Min-pi assassinations, etc. occured successively in Korea inside and outside of the country.

This is the outstanding travelogue, that faithfully tells the disquieting political situation of the Rhee Dynasty’s last years tossed about by the international situation

and the Korean natural face Bird saw such as the traditional climate, the folk customs and the cultural etc. that are left deeply in the Korea in the time right after Korea opened the country.

|

|

|

Lillias H. Underwood, “Fifteen Years among the Top-Knots or Life in Korea” (1904) Internet Archive

Internet Archive

Lillias Horton Underwood was born on June 21, 1851 in Albany New York. She went to Chicago to the Women’s Medical College (now a part of Northwestern University) to obtain a medical degree. She went to Korea as a medical missionary in 1888. Not long after her arrival in Chemulpo Korea, Lillias visited the queen who desired to secure the services of Lillias as her personal physician. In 1889 Lillias married Reverend Horace G. Underwood. Horace had already been in Korea for four years and knew how to arrange the trips through dangerous territory. They stayed in Japan from November of that year to May of the next year. Though most foreigners were distrusted in Korea, the Underwoods impressed the Korean officials and were allowed to take a journey to the far north. They traveled as missionaries without disguise. |

|

Angus Hamilton “Korea” (1904) Internet Archive

Internet Archive

Angus Hamilton (1874-1913) was a U. K.-born journalist and visited Korea in 1904 during Russo-Japanese War and went a little way further to in Mount Kumgang, Wonsan and the Ganghwa Island from Seoul. This book is quoted well to show development of Seoul before the merger of Korea and Japan. Bruce Cumings pointed out that such a development was dripped mainly by the American capital, and made a cynical remark on Korean double standard, “If it is by Japanese capital, that is colonization and if the capital except Japan, it is the modernization.” |

|

William Elliot Griffis, Corea the Hermit Nation (1905)

William Elliot Griffis (1843 – 1928) was an American orientalist, Congregational minister, lecturer, and prolific author.

In September 1870 Griffis was invited to Japan by Matsudaira Shungaku, for the purpose of organizing schools along modern lines. In 1871, he was Superintendent of Education in the province of Echizen.

Returning to the United States, in 1876 he publishes “The Mikado's Empire” that became the bestseller and he established the fame as the Orientalist.

The first edition of “Corea: the Hermit Nation” was published in 1882 and was sold well and went through nine editions by 1911.

Griffis had not visited Korea, and this book depends on existing documents written in English, French, German, Dutch, etc. and historical materials of Japan and China.

However, in the United States, it had the great influence as the first large Korea-related book, and the phrase “the Hermit Nation” became famous as a Korean pronoun.

|

|

Goro Arakawa, “Recent Korean affairs - Korean people” (1906) Digital collection of the National Diet Library, Japan (p.86-91)

Digital collection of the National Diet Library, Japan (p.86-91)

Goro Arakawa (1865 - 1944) is a Japanese politician, a journalist, a educationist, born in Hiroshima.

|

Korean people

|

Horace Newton Allen, “Things Korean: A Collection of Sketches and Anecdotes Missionary and Diplomatic” (1908) Internet Archive

Internet Archive

Horace Newton Allen 1858 – 1932) was a medical doctor and the first American Protestant missionary in Korea, arriving there in late 1884.

He served in Korea at the end of the Joseon Dynasty, becoming close to the emperor.

At his suggestion, in 1885 the emperor founded the institution that became known as Severance Hospital in Seoul (now in South Korea). It is now part of the Yonsei University Health System.

Due to Allen’s relationship with the emperor and other officials, Allen became part of the United States Legation to Korea:

he was appointed as secretary in 1890 and as US minister and consul general in 1897.

|

|

Frederick A. McKenzie, The Tragedy of Korea (1908)Frederick Arther McKenzie (1869~1931) was a Canadian born journalist who sympathized with Korean guerilla fought against Japan’s rule. McKenzie went to Korea to report Russo-Japanese war in 1904 for London Daily Mail. He visited Korea again in 1906 to contact Korean guerilla. After returning to London, he published The Unveiled East in 1907 and The Tragedy of Korea in 1908 for anti-Japan campaign. |

|

Homer B. Hulbert, “The Passing of Korea” (1909) Internet Archive

Internet Archive

Homer B. Hulbert (1863~1949) was an American theologian and journalist who helped Korean resistance against Japan. Hulbert first visited Korea in 1886 to teach at Yukweon Kongweon in Seoul. He once returned to the U.S. but visited again in 1893 to be an editor of Korea Review. In 1905, Hulbert tried to disturb the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty. In 1907, he tried to help Korean confidential emissaries participating in the Second Hague Conference. Because of this conspiracy, he could not reenter Korea during the Japanese regime. |

|

Governor-General of Korea, “The American tourist party’s view of Korean” -“Thoughts and character of the Korean” (1924)Digital collection of the National Diet Library, Japan (p.10-11) |

|

The American Clarks company sponsorship tourist party came to Keijō by arrival at Keijō Station down train at 8:00 a.m. on March 24, 1924.

It consisted of 40 American farmers including J. B. Baum.

They directly went to the Korea hotel and they visited Changdeokgung, Gyeongbokgung

and the other famous places with the guidance of three Korean interpreters attached to the hotel on the same day.

Next day 25th, they left there by down train 8:25 a.m. at Keijō Station toward Beijing. Three Americans including J. B. Baum expressed the following impression.

“It was concerned that Korea is always confused and there may be some danger for our trip under certain circumstances, but it was uneventfulness unexpectedly. That proves that the rule by Japan is all right. Thus, I see the greater strides of Korean culture than that of U. S. territory Philippines. The state that Korea is gradually Japanized should be called the success of the Japanese colonial policy. In my country I heard that the Korean mountains had no trees and plants, but I know that considerable trees grow thick in the fields and mountains now, when I see the situation along the railroad by this sightseeing. It must be also a gift of the Japan-Korea merger. In addition, when I am in Korea, I feel strange that the Korean is a race of the idleness. Some live like an animal on the street and some wander around the city in vain. There are many who play without doing anything. This naturally brings the ruin of a country.” (March, 1924) |

Governor-General of Korea, “Data №25 for investigation, Folk belief, The 1st - Korean fierce gods” (1929)Digital collection of the National Diet Library, Japan (p.441-463) |

The Korean eating and drinking method (superstition medical care)

|

William Franklin Sands, “Undiplomatic Memories: The Far East 1896-1904” (1930) Internet Archive

Internet Archive

William Franklin Sands (July 29, 1874 – June 17, 1946) was a United States diplomat most known for his service in Korea on the eve of Japan's colonization of that country.

William Franklin Sands (July 29, 1874 – June 17, 1946) was a United States diplomat most known for his service in Korea on the eve of Japan's colonization of that country.

|

|